Elaine Miles, CTUIR tribal citizen and beloved actress, first stepped into the spotlight when a simple ride to her mother’s audition led to her own breakout role on Northern Exposure. She has since brought her talent to The Last of Us and numerous other films and series.

By Gina Hill | Alaska Headline Living | December 2025

Indigenous actor Elaine Miles says a November encounter with men wearing Immigration and Customs Enforcement gear in Redmond, Washington, left her shaken and questioning how securely tribal citizens can move through public space in the Pacific Northwest. Miles, best known for her role as Marilyn Whirlwind on the television series “Northern Exposure” and more recently credited in “The Last of Us,” is an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) in northeastern Oregon.

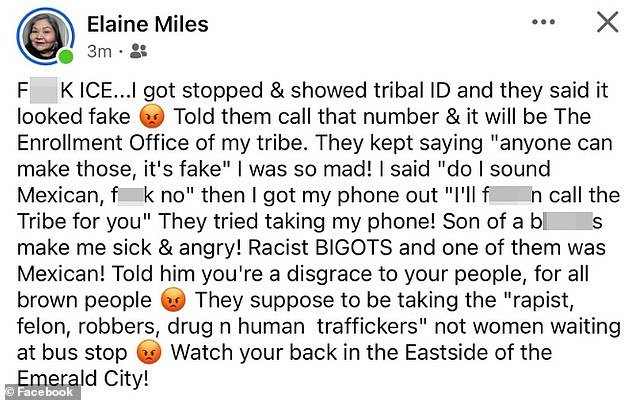

Facebook Post Sparks Outcry

The incident first became public when Miles wrote about it on her personal Facebook page, in a profanity‑laced post that was widely shared and later deleted. In the post, screenshots of which have been republished by multiple outlets, Miles described being stopped, having her tribal ID called “fake,” and accusing the men of being “racist bigots” who should be pursuing serious criminals instead of “women waiting at [a] bus stop.” Friends, colleagues and Indigenous advocates circulated the screenshots across platforms, helping push the story into regional and then national news coverage.

Miles’ Account of the Stop

In subsequent interviews with Native and Seattle‑area outlets, Miles said the encounter occurred on Nov. 19 as she walked to a bus stop near Redmond’s Bear Creek Village. She recounted that two unmarked black SUVs without front plates pulled up and four masked men wearing vests labeled “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement” approached her, demanded identification and asked if she was “legal.”

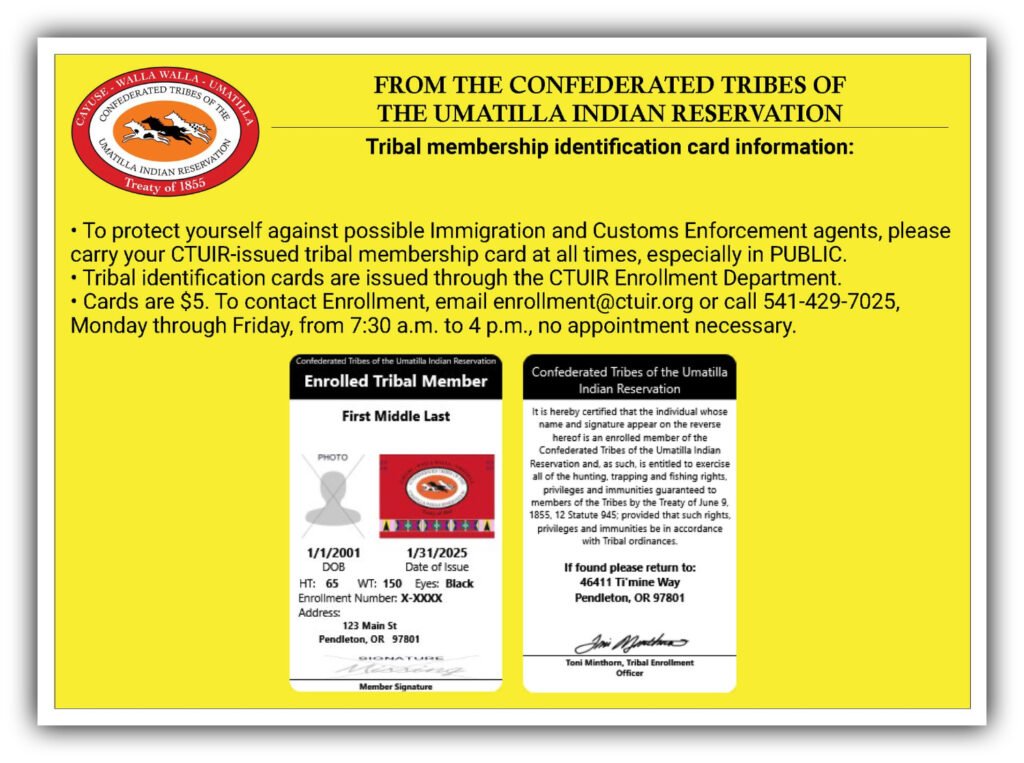

Miles said she handed over her CTUIR tribal membership identification card, which lists her as an enrolled tribal member and includes a phone number for the tribe’s enrollment office. According to her, the men repeatedly said the card “looked fake” and that “anyone can make those,” and refused her request that they call the phone number printed on the back to verify it. When she took out her own phone and tried to dial the number, she says one of the men grabbed for the device; moments later, another man by the vehicles whistled and the group abruptly left without arresting her.

Federal Agencies Respond

The Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement have acknowledged immigration‑enforcement activity in the Redmond area that day but disputed aspects of Miles’ description. A DHS statement said Miles was never arrested, transported or booked into custody and asserted that ICE officers are trained to recognize and accept tribal identification documents as valid under federal rules.

Officials have not publicly addressed Miles’ specific allegations about masked personnel in unmarked SUVs or why, if agents believed her documents were fraudulent, she was allowed to leave without further investigation. ICE has also not confirmed whether the men Miles encountered were agency employees, task‑force partners or impostors, leaving open questions that her attorney says demand an internal inquiry.

Rise in ICE impersonators adds uncertainty

Miles’ case is unfolding amid a documented rise in incidents of people impersonating ICE agents around the country. A 2025 analysis of court records and local reports identified roughly two dozen cases this year of individuals masquerading as ICE officers, more than during the previous four presidential administrations combined, with motives ranging from robbery and sexual assault to political intimidation of immigrants. In response, federal and local authorities in several states have issued public warnings about fake ICE officers approaching people in public places, sometimes wearing “ICE”‑marked clothing or tactical vests.

The FBI recently circulated a bulletin describing criminals who posed as immigration agents to carry out kidnappings, armed robberies and assaults, while California’s attorney general warned residents about “fake ICE officers” involved in scams and violent crimes and urged the public to verify credentials and report impersonation. Members of Congress have pressed DHS to ensure agents clearly identify themselves during operations, arguing that heavy use of masks, plain clothes and unmarked vehicles has created the kind of confusion that impersonators can exploit.

Tribal and legal advocates demand answers

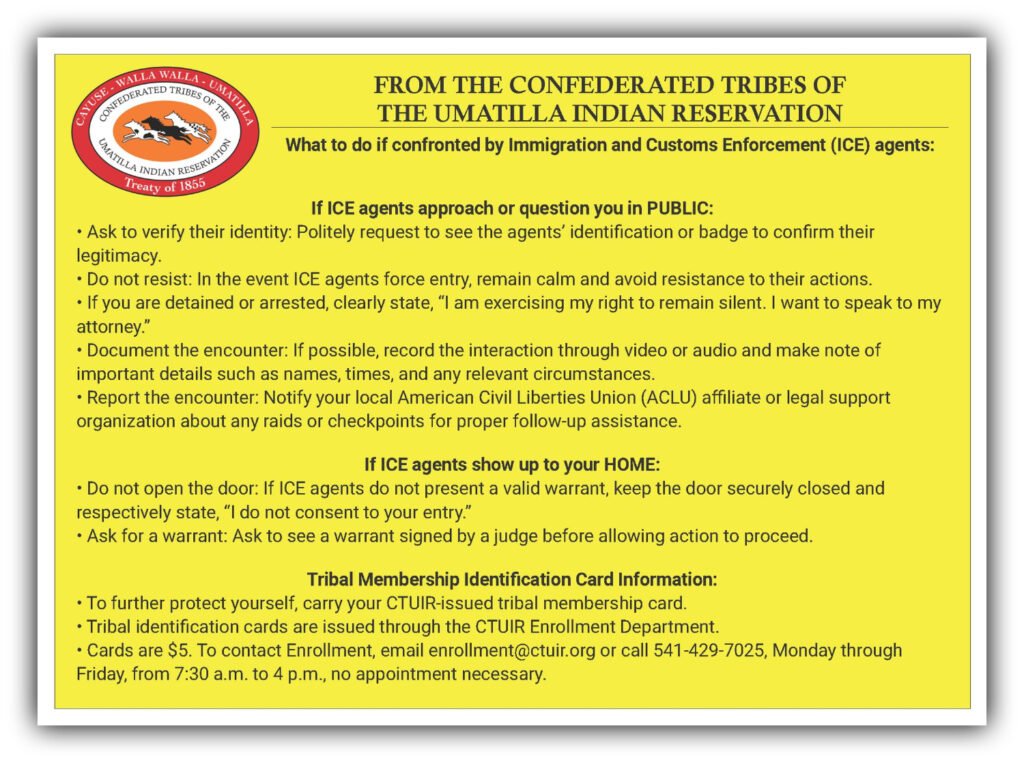

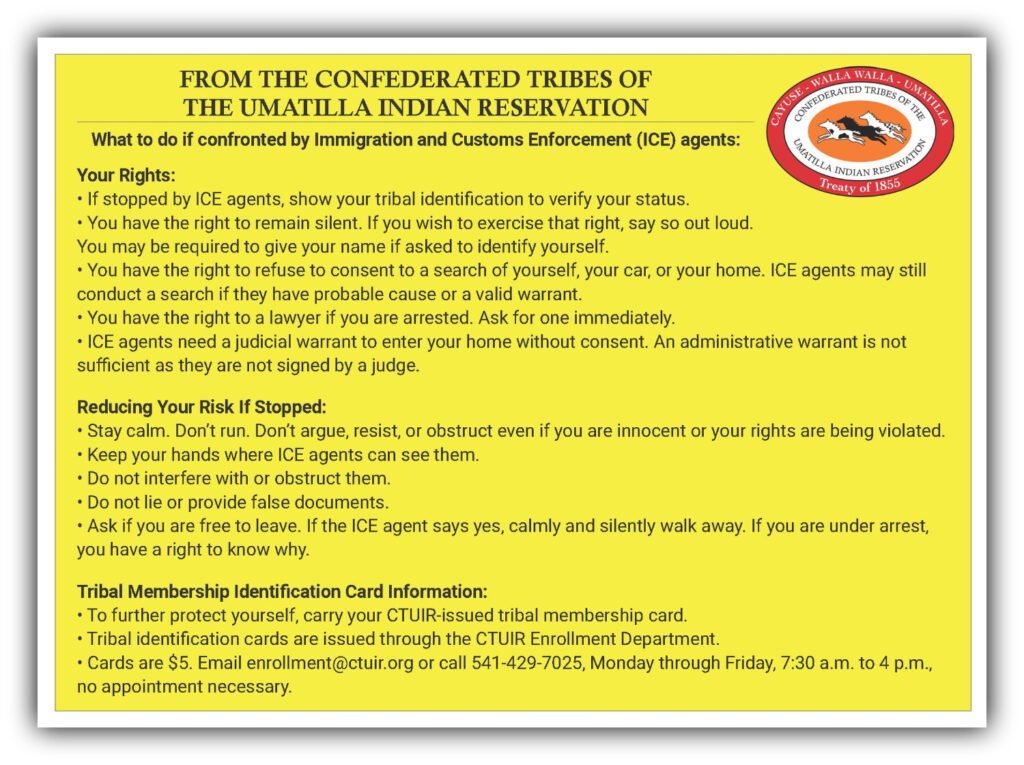

CTUIR leaders and Native‑rights advocates say Miles’ story highlights a broader, longstanding problem of law‑enforcement officers challenging or rejecting tribal IDs despite federal recognition of such documents. The tribe’s enrollment office has circulated guidance encouraging members to carry their CTUIR‑issued cards and providing contact information for officials who can verify tribal membership if questioned by authorities.

Seattle‑based attorney Gabriel Galanda, who represents Miles, has said the stop amounted to racial profiling and a failure to respect tribal sovereignty. He has called for an investigation into who stopped Miles, why her ID was dismissed and whether agents followed federal policy on the treatment of Indigenous citizens and tribal documents, particularly in light of the national trend of ICE impersonators.

Personal impact and wider implications

Miles has said the experience left her frightened to ride public transit alone and more cautious about traveling for work, adding that relatives have asked her to check in more often. She has also pointed to previous encounters in which her son and uncle were detained by immigration officers who initially questioned the validity of their tribal IDs before ultimately releasing them, arguing that these repeated incidents show the need for better training and accountability.

The episode unfolded during Native American Heritage Month, amplifying its symbolic weight for many Indigenous viewers and social media users. For Miles, whose acting career has often centered Native visibility on screen, the confrontation has become an off‑screen reminder that Native people can still find their identity and citizenship questioned in the very homelands where their nations predate the United States—sometimes by officers of the federal government, and sometimes, she now has reason to wonder, by those only pretending to be.

Confronted by ICE Agents? Here’s What to Do.

This informational notice from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Enrollment Office outlines steps CTUIR members can take to verify identity, document encounters, and assert their rights during interactions with federal authorities, including ICE. It emphasizes keeping enrollment records current, carrying valid identification, and knowing when agents need a judicial warrant to enter homes or workplaces.